The cookie wall, an increasingly common experience…

We’ve all had this experience when surfing the Internet: we want to access a particular site and a cookie banner appears, covering most of the screen and blocking access to the website’s content.

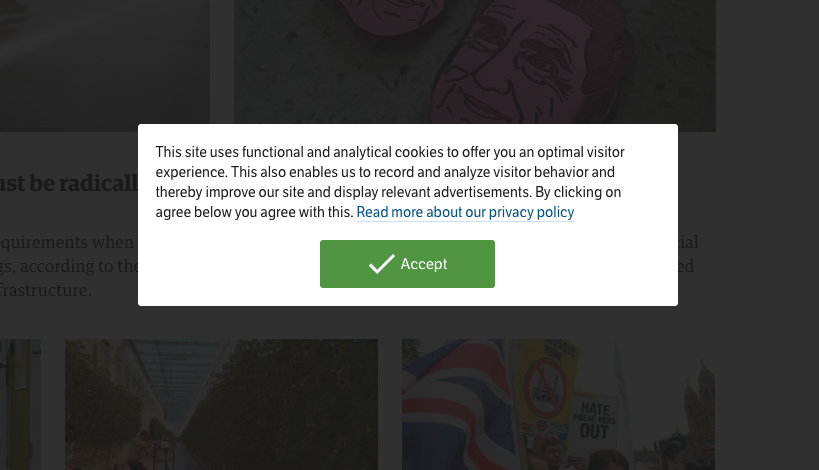

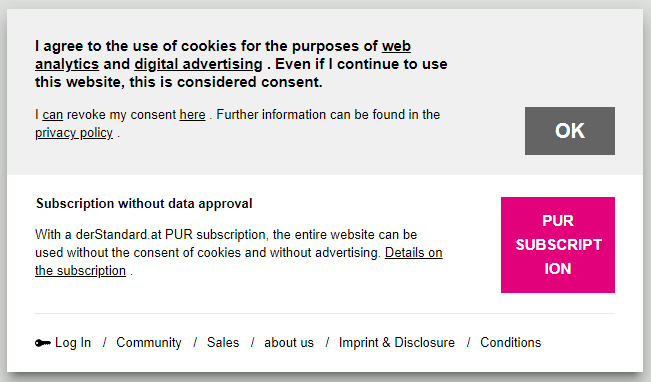

To disappear, the banner will generally give you a choice between two options:

- accept non-essential cookies (often those used for targeted advertising)

- refuse non-essential cookies and pay a fee (subscription or one-off payment) to access the site’s content.

This type of giant cookie banner is known as a “cookie wall“. Where a financial consideration is required, the term “paywall” is also used.

Cookie wall example: the user does not have the choice of accepting everything

Paywall example: the user must pay not to accept non-essential cookies

What is the aim of this practice?

To encourage visitors to accept non-essential cookies in order to access the site’s content, or possibly to ask them to pay a sum of money in order to access it without being tracked (and thus compensate for a loss of advertising revenue).

But is this really legal?

Assessing the legality of the cookie wall: information of interest to a wide range of players

As a website publisher, do you want to use this practice without the risk of being penalised?

As an organisation looking for a partner/service provider, do you consult other organisations’ websites to assess their seriousness and professionalism, particularly in terms of Eprivacy / GDPR compliance?

As a web agency creating websites, do you want to give your customers the best possible advice and avoid a complaint from them if they are penalised for a non-compliant site, or even get the contract they signed with you cancelled (and the money they paid you refunded)?

As a (future) customer of the company that publishes the website, would you like to assess whether it is trying to extort your data or money in an abusive manner?

As you will have realised, being able to assess the legality of a cookie wall gives you some interesting information, no matter what brings you to the site in question.

Legal framework

EPrivacy Directive

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the arrival of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that triggered the flood of cookie banners and repeated requests for consent on websites.

It was the EPrivacy Directive that laid down the rule governing the consent required to place (or read) “non-essential” cookies on an individual’s terminal (smartphone, tablet, smart TV, etc.).

In the case of the cookie wall, the website publisher is typically in a situation where it wishes to deposit/read cookies considered to be non-essential, given that the placement of a cookie wall is generally linked to advertising tracking.

The EPrivacy Directive specifies that for this type of cookie, there is no possible exception to the consent requirement, so the website publisher must obtain the visitor’s consent.

GDPR

When a website publisher collects information through the use of cookies, it is using/processing data that is considered to be personal data.

The GDPR therefore also has an impact on the way in which this data collection must take place.

More specifically, the GDPR will impose a certain quality on the consent provided for in the EPrivacy Directive. This consent will have to meet 4 criteria to be considered valid:

- Unambiguous

- Free (without constraint)

- Specific (the consent relates only to the use of the data in question and is not coupled with a consent to general conditions, for example)

- Informed (having clearly informed the visitor)

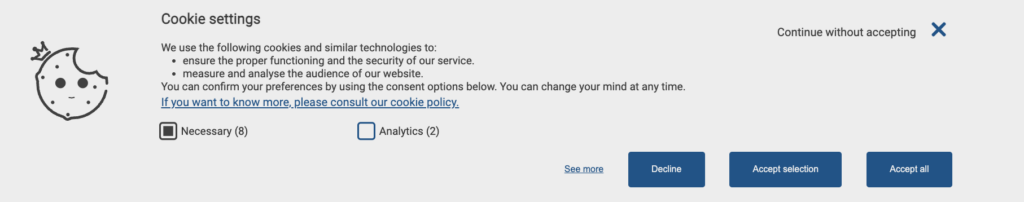

Visitors always have the right to change their mind and withdraw their consent. Withdrawing consent should be as easy as giving it (this can be assessed, for example, by comparing the number of “clicks” required to change their mind).

Cookie management button accessible on every page of the site so that visitors can change their mind

The main question raised by the use of a cookie wall to encourage visitors to accept “non-essential” cookies is as follows:

If visitors accept cookies to avoid having to pay a subscription fee, can their consent really be considered to be freely given, without constraint?

And that it is therefore valid under the GDPR?

Unfortunately, the data protection authorities that have examined this question are not unanimous.

… and uncertainties

While the GDPR is a European regulation that allows the same obligations to be applied to the various member states of the European Union (with a few specific exceptions), the Eprivacy Directive required national texts to be transposed locally, texts that allow states greater room for manoeuvre.

As a result, the way in which cookies and other trackers are managed is not entirely standardised.

If one day the draft Eprivacy regulation materialises, we may see more uniformity on the subject. In the meantime, we will have to assess the situation in each country.

The situation for organisations based in Belgium

The Data Protection Authority’s interpretation is simple: forcing visitors to a website to accept “non-essential” cookies (or a paid alternative) in order to access content is not considered to be free consent, and therefore not legal under the RGDPR.

The use of a cookie wall by Belgian sites is therefore prohibited.

The situation for organisations based in France

The Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) initially adopted the same position as its Belgian colleague, prohibiting the use of cookie walls.

Following a decision by the French Council of State (which considered that a general ban was disproportionate), the CNIL is now advocating a more nuanced approach.

Indeed, it prescribes a case-by-case analysis of the consideration required by the cookie wall in order to determine whether its use is authorised or not.

The website publisher wishing to install a cookie wall will therefore have to carry out an analysis based on various criteria:

- The existence of a fair alternative if the visitor wishes to refuse the tracers/cookies and does not wish to pay

- either by the website publisher

- or by another publisher

E.g.: it would be difficult for a public authority to justify making access to citizen services conditional on the fact that, by definition, it is the only one able to provide them.

With regard to the obligation to accept “non-essential” cookies in order to access content, when cookies are used for several purposes

- ensure that the obligation to accept cookies applies only to those purposes that enable payment for the service offered / access to content via the site and not to the acceptance of all cookies indiscriminately.

E.g.: enabling personalised content is a different purpose from being subject to targeted advertising.

- In relation to payment for access to content without depositing “non-essential” cookies

- the amount requested must be “reasonable”, also to be assessed on a case-by-case basis

- the payment format can also be selected to minimise the personal data required, for example by using virtual wallets (thus avoiding the need for visitors to provide bank details).

- With regard to the possible obligation to create a user account to access content

- ensure that this obligation is justified (e.g. to allow access to content on different platforms)

- of course, comply with the other principles of the GDPR (informing internet users, collecting only necessary data, etc.).

The situation for organisations based in Germany

The DSK (the assembly of German data protection authorities) considers that the use of a cookie wall is possible provided that an alternative without “non-essential cookies” is available to the website visitor.

The fact that this alternative has to be paid for is not a problem in itself and does not prevent consent from being freely given, provided that the following conditions are met:

- The paid alternative must provide the same benefits/services as the “free with non-essential cookies” version;

- The amount charged for access to the site’s content must be in line with market practice for equivalent services.

The situation for organisations based in Italy

The Garante, the Italian data protection authority, states in its guidelines that the use of a cookie wall to obtain consent to the deposit of “non-essential” cookies is not considered to be free consent.

An exception would be possible if the site allows the visitor to access equivalent content without having to consent to the deposit and use of “non-essential” cookies. As in France, this would be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

In all cases, the Garante insists on the importance of transparency in the way information is communicated to visitors regarding the use of cookies and other tracking devices.

Our advice if you want to use a cookie wall on your website

At present, each Member State of the European Union is free to choose its position on the matter.

If you are in the situation where you wish to use a cookie wall (not in Belgium, therefore), ask yourself the following questions:

- In which country are you located, as the publishing body responsible for the website?

- What is the position of the local data protection authority?

In order to anticipate problems, we recommend that you always :

- Carry out your detailed analysis in writing, so that you can easily demonstrate that you have carried it out (and possibly updated it as your context changes) as required by the GDPR principle of responsibility;

- Have this analysis validated by your organisation’s administrative body (if you do not have the legal capacity to commit it);

- Anticipate a justification text to be provided on request to visitors to your website (in order to defuse the conflict and avoid a complaint);

- Include elements of justification in your cookie management policy (or directly on the banner) to demonstrate greater transparency to visitors to your website;

Conclusion

As you will have realised, the very design of your cookie banner and the wording of the information communicated to visitors will play an important role in assessing the legality of the cookie wall.

We would therefore like to add one last piece of advice for the road, valid for any cookie banner but all the more sensitive in the case of a case-by-case analysis of the legality of a cookie wall:

Avoid the still widespread practice of misleading your visitor, by using deceptive interfaces / dark patterns, which are ways of coming into conflict with the GDPR, in the design of your banner.

Please note: these dark patterns are not limited to the graphic elements or structure of your cookie banner, but can also be found in the text.

For example, making visitors feel guilty about their decision to refuse targeting cookies can be considered as “shaming”, a type of dark pattern.

A visitor who feels cheated is a visitor who loses confidence, a prospect who will not sign the contract, an individual who turns to associations such as NOYB to defend his rights.

And that, whatever the final outcome, is never good for business.

At Admeet, we have chosen to offer you user-friendly cookie banners that are not oppressive, in order to inform your visitors transparently about the way in which you are going to collect and use their personal data via cookies and other tracers.

Admeet cookies banner

Would you like to discover our 100% Legal Design banners?